Medieval parchments

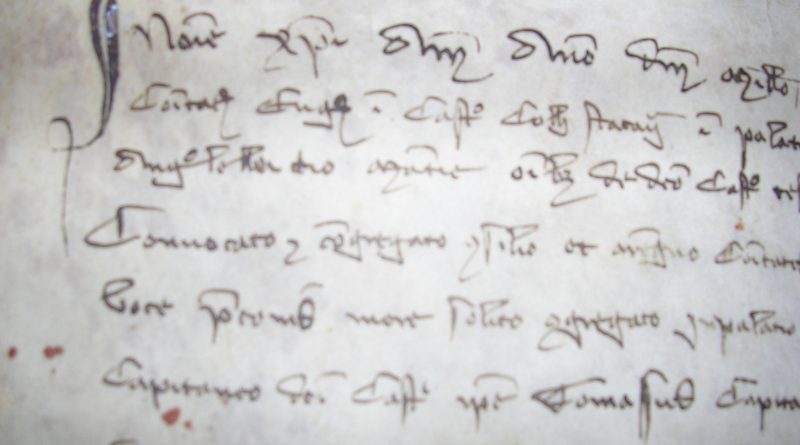

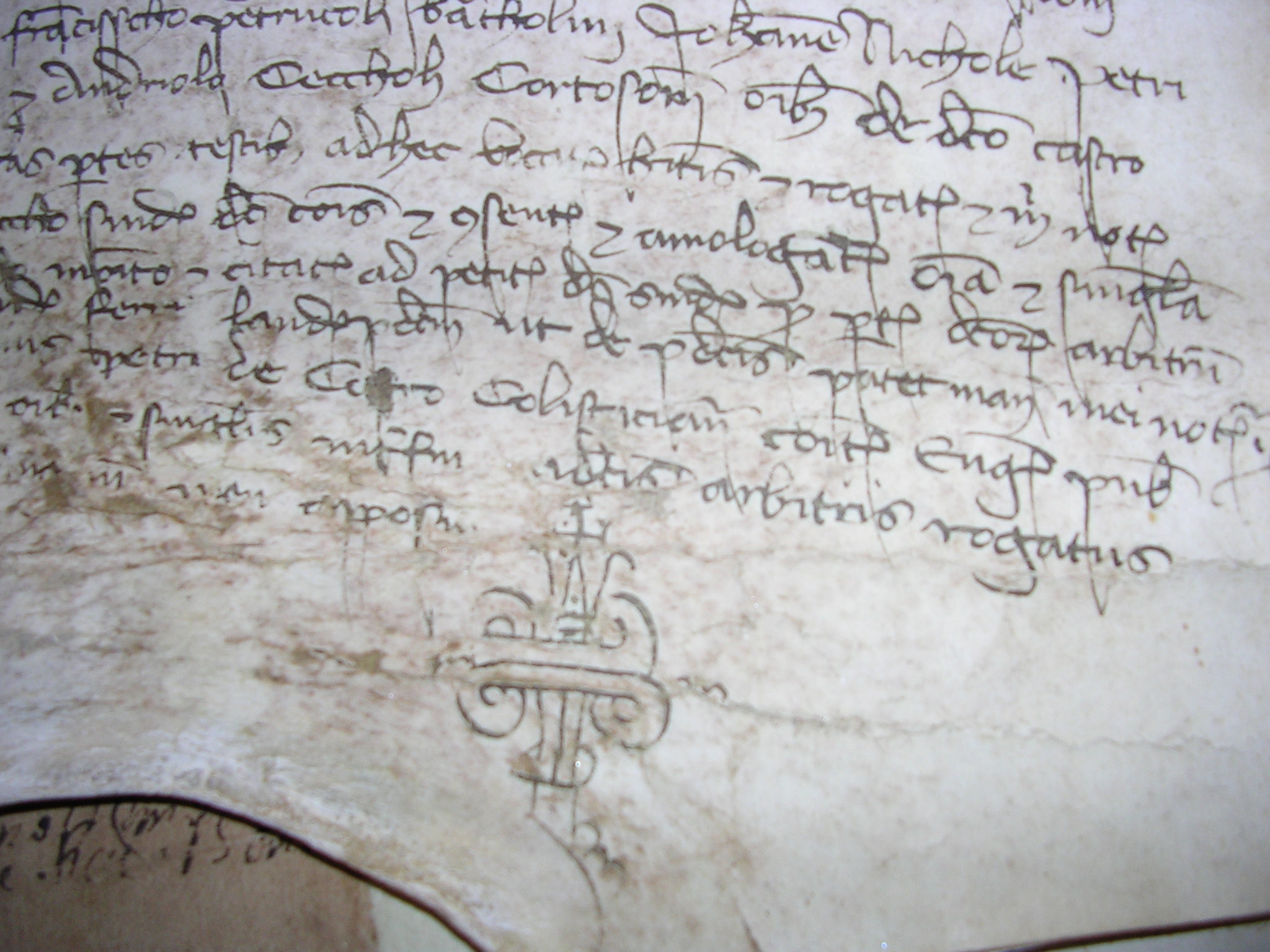

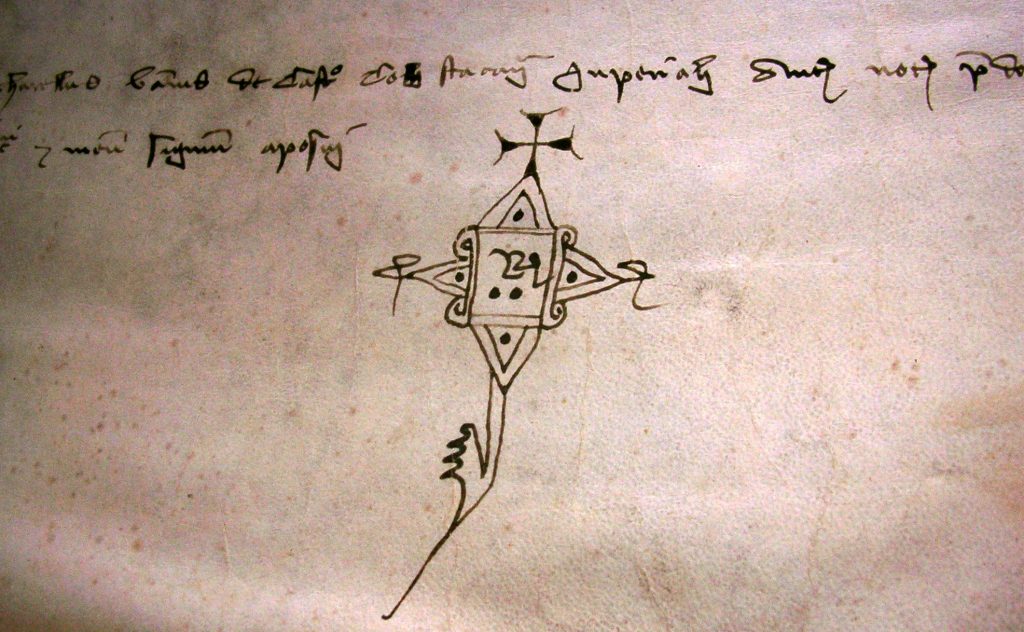

Some scrolls found in the archives of the monasteries of Santa Giuliana (Saint Juliana) and San Domenico (Saint Dominic) in Perugia, indirectly provide some very useful information to help us understand the status of women in the late Middle Ages.

The documents found, in fact, seem to confirm that women held a relatively autonomous social role within the medieval family and within the society of the thirteenth century as a whole.

An analysis of the scrolls, dating back to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, shows that women of Perugia and the surrounding countryside were able to buy property, manage land, pay taxes, make leases, and even sign wills.

We find also that even if a dowry was a prerequisite for entering into a marriage, the wife did not lose all of her property rights as a result of the marriage. In fact, in the event of widowhood, the wife would again possess the properties that were hers prior to entering into the marriage.

This is amply demonstrated by a document signed in Perugia in 1300, stating that a man named Vegna received, from his brother in law Cescho, the sum of 125 denari pisani piccoli (denaro pisano was a medieval coin) as dowry for his wife Charutia, sister of Cescho. In the document Vegna states that: “per tale matrimonio, contratto secondo la legge longobarda, aveva già donato a Cescho, ricevente per la sorella, 31 libre e 5 soldi della detta moneta, come quarta parte dei suoi beni che la moglie avrebbe dovuto tenere in caso di vedovanza” ( for his marriage to Charutia, Vegna had received from Cescho the sum of 31 libre e 5 soldi, that Charutia would receive in return in the event of her husband Vegna’s death). In other words, the medieval document stipulates the rights of the bride (Cescho’s sister) in the eventuality of her widowhood.

This document seems to reveal that family property in the late Middle Ages was administered by the pater familias (head of household) along with his wife, whose role was more of a manager, rather than that of a true owner. In fact, the documents show that spouses often worked in partnership, administering their households together. This is also evidenced by a deed, signed in 1269 at Gubbio, where Jacobus Benedictoli along with his wife, Rustica Marci, sell to “Bonaore Salvali un pezzo di terra … al prezzo di 17 libre di denari ravennati e anconetani “ (stipulating the sale of a strip of land to Bonaore Salvali). The document reveals that the deed would not be deemed valid without the consent of the wife!

The same phenomenon is apparent in a document, drawn up in 1260 in Perugia, where Giliuccio sells a piece of land with vineyard, also on behalf of his wife Dialdana. The woman’s consent was signed with the words “Domina Dialdana, uxor Giliutii et filia Lancelocti, consente alla vendita di cui sopra.”(by consenting to terms stated above in the document, lady Dialdana, wife of Giliuccio and daughter of Lancillotto, essentially consents that the land with vineyard would be sold).

Sales, leases and wills could also occur between women, without intervention of men. In 1340, in Perugia, a woman named Tadea rents a piece of land for three years to another woman named Clara from Villa di Pian del Carpine (this is the medieval name of the village corresponding to the town of Magione, close to lake Trasimeno).

And in her will, a woman named Bartola, daughter of Bentivegna, wife of Gigio, and mother of the nun Suor Margherita who is living in the monastery of Saint Julian in Perugia, states that several of her possessions will be left to the following women: “… domina Massaria Guillelmi, domina Angeluzia Berardini, domina Lucia de Genua , Ceccola, Vanna, Mita, domina Agnese e a suor Margherita del monastero di Santa Giuliana sua figlia legittima.” In the same document Domina Bartola also appoints her future children, if any, as heirs, and in the case she doesn’t have more children, her husband is named as heir.

Author: Antonella Bazzoli

Translated by Lynn De La Torre, August 15th 2012