The Tree of Life is within us

A few nights ago, as he ate a lemon slowly bite by bite, my son unintentionally swallowed a seed along with the fruit of the lemon, and then exclaimed soon thereafter: “That’s okay, all it means is that I will grow the tree of life in my stomach!” (Va bene, vorrà dire che mi crescerà nello stomaco l’albero della vita!)

The sagacity of this proclamation, made by a child of only 10 years old, affected me so deeply that the next morning, as I awoke, I realized that I had connected my dream from the night before to my son’s profound exclamation. My dream was about the episode within the Epic of Gilgamesh where the hero goes in search of the fruit of the Tree of Life.

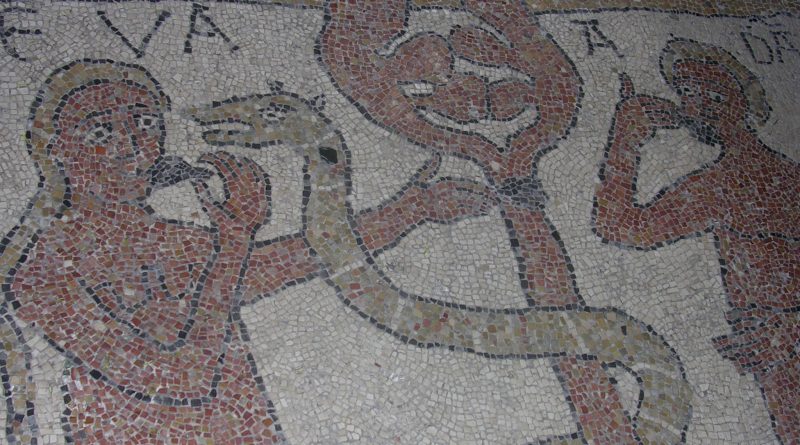

In the poem from ancient Mesopotamia “The epic of Gilgamesh”, that dates back to about 5000 years ago, the king of Uruk, Gilgamesh was devastated by the death of his beloved friend Enkidu. Unable to accept the idea of Death, the king decides to go in search of a plant that could make him young again. After many vicissitudes and a meeting with the deity who tries in vain to discourage him in this enterprise, the protagonist reaches the sage Utanapishtim, who having tried in vain to convince the hero to give up his search, takes pity on him and informs him of a special plant that grows only at the bottom of the sea that could make him young again. Gilgamesh dives into the Apsu (the marine abyss where the god Enki, the lord of the underworld, dwells), and reaches the fruit of the Tree of Life and with it in hand he rises to the surface, getting rid of the symbolic gifts of power Pukku and Mekku ( drum and drumstick) that had served as ballast in his descent.

On the way back to Uruk, the hero stops to rest and places the plant on the shore of a lake while he bathes, but a snake smelled and promptly devours the plant, thereby shedding its old skin and being reborn into a new life. At this point in the text one reads: “Gilgamesh sat down and wept, tears streaming down his cheeks. (…) What purpose does the last blood in my veins serve? I have not been able to get anything good for myself.” The hero has become aware: a life that lasts forever is not his destiny.

But perhaps the Tree of Life symbolically also represents something else: the vital dynamism constantly evolving and changing, the ability to ascend to heaven, the connection between earth and sky, between matter and spirit.

We find in this sense the archetype of the Tree of Life in many ancient cultures. Some examples of references: images within meditation, the biblical Tree of Life that is planted in the middle of the Garden of Eden, and the Cross of Christ which medieval legends held to be made from the wood of the Tree of Life.

So, I believe that this universal and archetypical symbol represents our own perennial cycle of “life / death / life”, the natural cycle that belongs to the material sphere of our reality, but that it also represents transcending that reality, and ought not to be sought outside of ourselves. It seems useless to look for the “Tree of Life” outside this plane of reality. To search for it outside of ourselves strikes me as an unsuccessful search.

I feel that the answer to the mystery of Eternal Life is not external to our being, rather it is ever-present and exists within each of us. The Tree of Life lies within us, and is part of our deepest self, hidden at the bottom of an abyss we can achieve only if we “descend” consciously towards our origins, to the depths of our roots …

I think that the story of the descent into Apsu by Gilgamesh parallels the episode of the “descent into hell” by Christ, as reported by Matthew in the New Testament: “For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of a huge fish, so the Son of Man will be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth ” (Matthew 12:40).

Another interesting comparison can be found in the book of Ephesians where Saint Paul, referring to the three days between death and resurrection of Jesus, says: “What does he ascended mean, except that he also descended to the lower, earthly regions?” (Ephesians 4:9).

Similar “Descents into hell” are also referenced in traditions much older than Christianity. There are many ancient myths concerning Afterlife travels and Descents to the Underworld, made by heroes and Gods.

The connection with certain rituals of the death and rebirth of nature is evident, as envisioned by the initiates of the ancient traditions such as Mithraism and Eleusinian mysteries

Hades abducted Persephone in the Underworld and her mother Demeter wandered all over the earth looking for her daughter, forbidding the trees to bear fruit… A journey to the Afterlife was made also by Orpheus who tried in vain to bring his wife Eurydice back from the dead…

Theseus, Hercules and Dionysus also went down into the Underworld to find their own divine identity… Then, there is also Ulysses, who descends into the Underworld to learn from Tiresias if he will ever succeed in ending his trip and if he will ever return to Ithaca (Odyssey XI, 90-137).

Enea also descends among the dead, accompanied by the Sibyl, to find his father Anchises (Aeneid VI, 237-31).

All of these examples are metaphors for inner journeys, in my opinion. They are myths that help us to understand the importance of our capability as human beings to “descend” within ourselves on a trip to the depths of our roots, where we can find the symbolic Tree of Life and return victorious free of any ballast (Pukku and Mekku), just like the hero Gilgamesh, awakened and aware of our own destiny and divine nature.

by Antonella Bazzoli – translation by Lynn De La Torre – April 25 2016 –